House automation tooling - Part 3 - London-School and Double-Loop

Last post was more research and about prototyping some code related to how the serial communication can work using actors.

In this post we start the project with a first use-case. We'll do this using a methodology called "Outside-in TDD" but with a double test loop.

Outside-in TDD (London School)

There are a few variants of TDD. The classic one, which usually does inside-out, is called Classic TDD also known as "Detroit School", because that's where TDD was invented roughly 20 years ago. When you have a use-case to be developed, sometimes this is a vertical slice through the system maybe touching multiple layers, then Classic TDD starts developing at the inner layers providing the modules for the above layers.

Outside-in TDD also known as "London School" (because it was invented in London) goes the opposite direction. It touches the system from the outside and develops the modules starting at the outside or system boundary layers towards the inside layers. If the structures don't yet exist they are created by imagining how they should be and the immediate inner layer modules are mocked in a test. The test helps define and probe those structures as a first "user". Outside-in is known to go well together with YAGNI (You Ain't Gonna Need It) because it creates exactly the structures and modules as needed for each use-case, and not more. Of course outside-in TDD is still TDD.

Double loop TDD

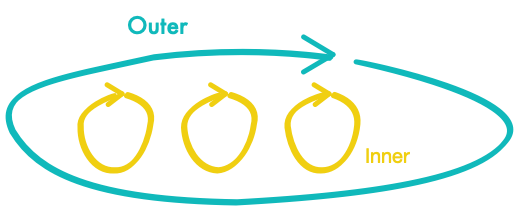

Here we use outside-in TDD with a double test loop, also known as Double Loop TDD.

Double Loop TDD creates acceptance tests on the outer test loop. This usually happens on a use-case basis. The created acceptance test fails until the use-case was fully developed. Doing this has multiple advantages. The acceptance test can verify the integration of components, acting as integration test. It can also check against regression because the acceptance criteria are high-level and define how the system should work, or what outcome is expected. If that fails, something has gone wrong. This kind of test can be developed in collaboration with QA or product people.

Double Loop TDD was first explained in detail by the authors of the book Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests. This book got so well-known in the TDD practicing community that it is just known as "GOOS".

Let's start with this outer test

Our understanding of the first use-case is that we send a certain command to the boiler which will instruct the boiler to send sensor data on a regular basis, like every 30 seconds. The exact details of how this command is sent, or even how this command looks like is not yet relevant. So far we just need a high-level understanding of how the boiler interface works. An expected result of sending this command is that after a few seconds an HTTP REST request goes out to the openHAB system. As a first start we just assume that there is a boundary module that does send the REST request. So we'll just mock that one. Later we might wanna remove all mocking from the acceptance test and setup a full web server that simulates the openHAB web server. It is likely that the acceptance test also goes over multiple iterations until it represents what we want and doesn't use any inner module structures directly.

(defvar *path-prefix* "/rest/items/")

(test send-record-package--success--one-item

"Sends the record ETA interface package

that will result in receiving sensor data packages."

(with-mocks ()

(answer (openhab:do-post url data)

(progn

(assert (uiop:string-prefix-p "http://" url))

(assert (uiop:string-suffix-p

(format nil "~a/HeatingETAOperatingHours" *path-prefix*)

url))

(assert (floatp data))

t))

(is (eq :ok (eta:send-record-package)))

(is (= 1 (length (invocations 'openhab:do-post))))))So we're still at Common Lisp (non Lispers don't worry, Lisp is easy to read). Throughout the code examples we use fiveam test framework and cl-mock for mocking.

with-mocks sets up a code block where we can use mocks. The package openhab will be used for the openhab connectivity. So, however the internals work, eventually we expect the function do-post (in package openhab, denoted as openhab:do-post) to be called with an URL to the REST resource and the data to be sent. As our first iteration this might be OK. This expectation can be expressed with answer. answer takes two arguments. The first is the function that we expect to be called. We don't know yet who calls this and when, or where. It's just clear that this has to be called.

Effectively this is what we have to implement in the inner test loops. When this function is expressed like here (openhab:do-post url data) then cl-mock does pattern matching on the function arguments and it allows the arguments to be captured as variables url and data. This enables us to do some verification of those parameters in the second argument of answer, which represents the return value of do-post. So yes, we also define what this function should return here and now in this context. The return value of do-post here is t (which is like a boolean 'true' in other languages) as the last expression in the progn (progn is just a means to wrap multiple forms where only one is expected. The last expression of progn is returned). The assertions inside the progn do verify that the URL looks like we want it to look and that the data is a float value. Perhaps those things will later slightly change as we understand more of the system.

Sending data to openHAB is the expected side-effect of this use-case. The action that triggers this is: (eta:send-record-package). This defines that we want to have a package eta which represents what the user "sees" and interacts with (the UI of this utility will just be the REPL). So we call send-record-package and it should return :ok.

At last we can verify that do-post got called by checking the recorded invocations of cl-mock.

And of course this test will fail.

It is important that we go in small steps. We could try to code all perfect the first time, but that doesn't work out. Things will be too complex to get right first time. There will be more iterations and it is OK to change things when appropriate and when more things are better understood.

What's next

Next time we'll dive into the inner loops to satisfy those constrains we have setup here.

-

[Polymorphism and Multimethods]

02-03-2023 -

[Global Day of CodeRetreat - recap]

07-11-2022 -

[House automation tooling - Part 4 - Finalized]

01-11-2022 -

[House automation tooling - Part 3 - London-School and Double-Loop]

02-07-2022 -

[Modern Programming]

14-05-2022 -

[House automation tooling - Part 2 - Getting Serial]

21-03-2022 -

[House automation tooling - Part 1 - CL on MacOSX Tiger]

07-03-2022 -

[Common Lisp - Oldie but goldie]

18-12-2021 -

[Functional Programming in (Common) Lisp]

29-05-2021 -

[Patterns - Builder-make our own]

13-03-2021 -

[Patterns - Builder]

24-02-2021 -

[Patterns - Abstract-Factory]

07-02-2021 -

[Lazy-sequences - part 2]

13-01-2021 -

[Lazy-sequences]

07-01-2021 -

[Thoughts about agile software development]

17-11-2020 -

[Test-driven Web application development with Common Lisp]

04-10-2020 -

[Wicket UI in the cluster - the alternative]

09-07-2020 -

[TDD - Mars Rover Kata Outside-in in Common Lisp]

03-05-2020 -

[MVC Web Application with Elixir]

16-02-2020 -

[Creating a HTML domain language in Elixir with macros]

15-02-2020 -

[TDD - Game of Life in Common Lisp]

01-07-2019 -

[TDD - classicist vs. London Style]

27-06-2019 -

[Wicket UI in the cluster - reflection]

10-05-2019 -

[Wicket UI in the Cluster - know how and lessons learned]

29-04-2019 -

[TDD - Mars Rover Kata classicist in Scala]

23-04-2019 -

[Burning your own Amiga ROMs (EPROMs)]

26-01-2019 -

[TDD - Game of Life in Clojure and Emacs]

05-01-2019 -

[TDD - Outside-in with Wicket and Scala-part 2]

24-12-2018 -

[TDD - Outside-in with Wicket and Scala-part 1]

04-12-2018 -

[Floating Point library in m68k Assembler on Amiga]

09-08-2018 -

[Cloning Compact Flash (CF) card for Amiga]

25-12-2017 -

[Writing tests is not the same as writing tests]

08-12-2017 -

[Dependency Injection in Objective-C... sort of]

20-01-2011